Gershom Gorenberg trägt eine Kippah und einen Bart. Er ist offensichtlich orthodoxer Jude. Und er steht politisch links. Ziemlich weit links. Wer gerne in Schwarz-Weiß-Schubladen denkt, wird mit Gershom Gorenberg nichts anfangen können. Allen anderen empfehle ich hier den Beitrag nachzulesen oder nachzuhören, der als Teil 2 einer Serie im Deutschlandfunk gesendet wurde – und zwar bei „Tag für Tag. Aus Religion und Gesellschaft“.

Das Thema:

„Die Synagoge prostituiert sich“: Warum orthodoxe Juden Religion und Staat in Israel stärker trennen wollen. Ein Gespräch mit Gershom Gorenberg

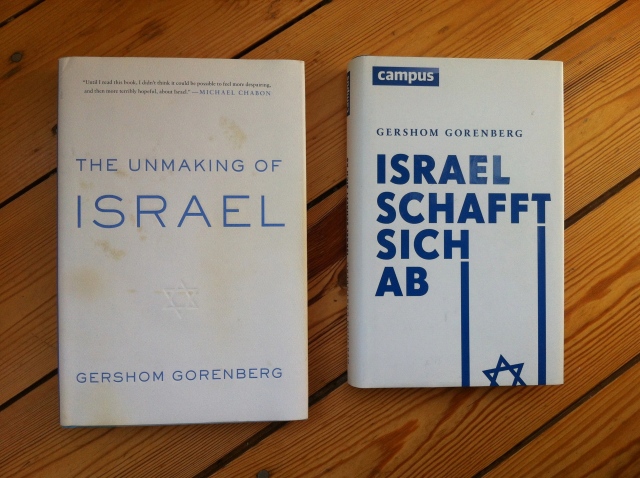

Gershom Gorenberg ist Historiker und Journalist, Autor mehrerer Bücher. Er stammt aus den Vereinigten Staaten, lehrt auch regelmäßig an US-Universitäten, lebt aber seit fast 40 Jahren in Israel. Gershom Gorenberg versteht sich als orthodox und als Zionist, kommt aber auf der Basis der jüdischen Tradition zu ganz anderen politischen Positionen als etwa die Regierungen seines Landes oder als national-religiöse Siedler. Ich habe Gershom Gorenberg in einem Cafe in Jerusalem getroffen, jenen Mann, der sich selbst als „jüdisch-orthodox und skeptisch, zionistisch und links“ beschreibt und dessen jüngstes Buch „The Unmaking of Israel“ heißt – mit dem deutschen Titel „Israel schafft sich ab“:

Die Bücher von Gorenberg beschäftigen mich nun seit rund zwei Jahren. Der Titel des jüngsten Werks mag düster klingen. Aber das, was Michael Chabon über dieses Buch geschrieben hat, kann ich teilweise unterschreiben:

„Until I read this book, I didn’t think it could be possible to feel ore despairing, and then more terribly hopeful, about Israel.“

„The Unmaking of Israel“ würde ich unbedingt der deutschen Fassung vorziehen: „Israel schafft sich ab.“ Auf einer der letzten Seiten war der Übersetzer offenbar so ermattet, dass er Gorenberg von einer „Trennung von Staat und Kirche“ reden lässt, wiewohl dieser von „religion and state“ schreibt. Ich weiß, dass Übersetzer von Sachbüchern wenig verdienen, aber dass Juden neuerdings Kirchenmitglieder sind, war bisher an mir vorbeigegangen.

Richtig stark ist auch: „The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967-1977“. Dies ist aber deutlich komplexer und nicht auf Deutsch erschienen. Ich stecke mitten drin. Ich würde also erst die Lektüre von „Unmaking of Israel“ empfehlen, danach „The Accidental Empire“.

Als Bonus-Material hier noch ein paar Originalzitate, wiewohl ich in amerikanischer Zeichensetzung nicht allzu firm bin:

„What would destroy a jewish state? It’s – in simple terms – continuing the occupation to the point where there is inevitable no other choice except for annexation and full citizenship for everybody who lives between the river and the sea, at which point the Jews become a minority, at which point there is no longer self-determination for the Jews as a people.“

„Everything I am saying here I’m saying as a religious Jew, as an orthodox Jew, as somebody who believes that is very important to keep, continue, develop the jewish religion. The reason that these issues concern me is not only because of the political impact, but because I’m deeply concerned about the impact on religion which is the most basic thing in my life.“

„Look, first of all, I’m left of center politically. I use the term orthodox as short hand, because that’s the term that people use. I think, that it is actually a borrowed term from other cultures, and it does not fit the jewish context, because orthodox means right-thinking. And in certain other religious context, the right belief is the core argument of the religion – and in Judaism people can have many different theological interpretations. And what holds the religious community together is shared practice. So, it is more correct for me to say, I am a halachic Jew, which is to say, I am somebody who strives to live my life according to Halacha, according to the jewish tradition of how one should live one’s day-to-day-life.“

„I think, inevitably, state sponsored religion corrupts religion. What it does: It puts a state bureaucracy in charge of making religious choices. And this both subjects the religion to political power plays, patronage and all the other aspects of statehood. And it separates religion from the public. In a situation where there is a separation of state and religion, the religious bodies cannot count on the state for support. They have to actually be relevant to the people. When the state underwrites religion, two things happen: One is, religious authorities appointed by the state, are not actually responsible to the public directly, they don’t have to make religion relevant or answer the needs of the public; and second of all, it allows the state for political reasons, which maybe divorced entirely from religion, to choose who the proper clerics are and the proper way of carrying out religion is. So, as much as established religion is a bad idea for civil rights and for the state, it is also a bad idea for religion.“

„The state is also choosing which orthodox rabbis will represent orthodoxy. And it is giving those rabbis the opportunity to interpret Judaism which has multiple interpretations without being responsible to the general public. And so they are much more likely to look over their shoulder and see what other people in the most conservative parts of the clergy think of their decisions than to think how this effects the life of people in the country. Because they are not actually directly responsible. They are responsible to a hierarchy, that is interlocked with the state. And who gets these positions often comes out of coalition agreements and party politics. So the result is that what appears to be orthodox Judaism as represented through the state’s structure is a narrow, and I would say very distorted form of orthodoxy as well. And this is incredibly damaging for the flourishing of religion.“

„The medium is the message. The sacred text is an argument about meanings, not a single meaning. Therefore the person who is involved in the act of study is also inevitably, I would say, religiously obligated to be making choices between interpretations. It would be false consciousness within the structure of Judaism to claim, that I am doing this because the text imposes it on me and there is no other interpretation of the text. Because there is always another interpretation of the text. And multiple interpretations are part of the same tradition. And that is also why having a power structure of a state choose one interpretation is essentially unjewish.“

Hier noch der Überblick über die gesamte Serie:

15.9.2014 Die Hebräisch sprechenden Katholiken in Israel: Porträt einer Gemeinde, die einzigartig ist in der Kirchengeschichte.

16.9.2014 „Die Synagoge prostituiert sich“: Warum orthodoxe Juden Religion und Staat in Israel stärker trennen wollen. Ein Gespräch mit Gershom Gorenberg

17.9.2014 Weltliche Talmud-Schulen: In Israel wächst eine Bewegung, die auch Nicht-Religiösen jüdische Werte und Traditionen vermitteln will.

18.9.2014 „Gott will diese Vielfalt“: Der israelische Rabbiner David Rosen und sein interreligiöses Engagement.